Maximizing the Working Properties of Orthodontic Archwires

Maximizing the Working Properties of Orthodontic Archwires

Long before there was the Damon System, which brought the idea of self-ligating braces and faster treatment into the mainstream, George & Fred Schudy sought to maximize light forces and favorable wire properties during initial alignment1. They realized that while the greater range and lighter forces offered by nickel titanium archwires provide significant treatment advantages, the wires alone were only a partial step forward toward increased efficiency. Their conclusion was that we must consider basic changes to the bracket systems themselves.

The Schudy article established 3 criteria that appliances must leverage to maximize the working properties of orthodontic wires:

- Increasing interbracket distance

- Small, flexible initial archwires

- As much intra-bracket play around initial wires as possible

A bracket system that meets these requirements would maximize the expression of desirable wire characteristics and increase alignment efficiency.

Passive Self-Ligation Increases Treatment Speed?

The findings in this study that intrabracket space has nearly as much impact on the clinical workings of an orthodontic appliance as does interbracket distance is a particularly important discovery. However, despite acknowledging that intrabracket space also reduces friction between the bracket and the wire, making leveling faster and easier, they found it difficult to resolve the puzzle between increased intrabracket play and regaining control using traditional edgewise appliances1. Their solution to this paradox at the time was a bimetric appliance utilizing single-wing brackets and differential slot sizing; however, passive self-ligating brackets now provide a particularly elegant solution to this dilemma.

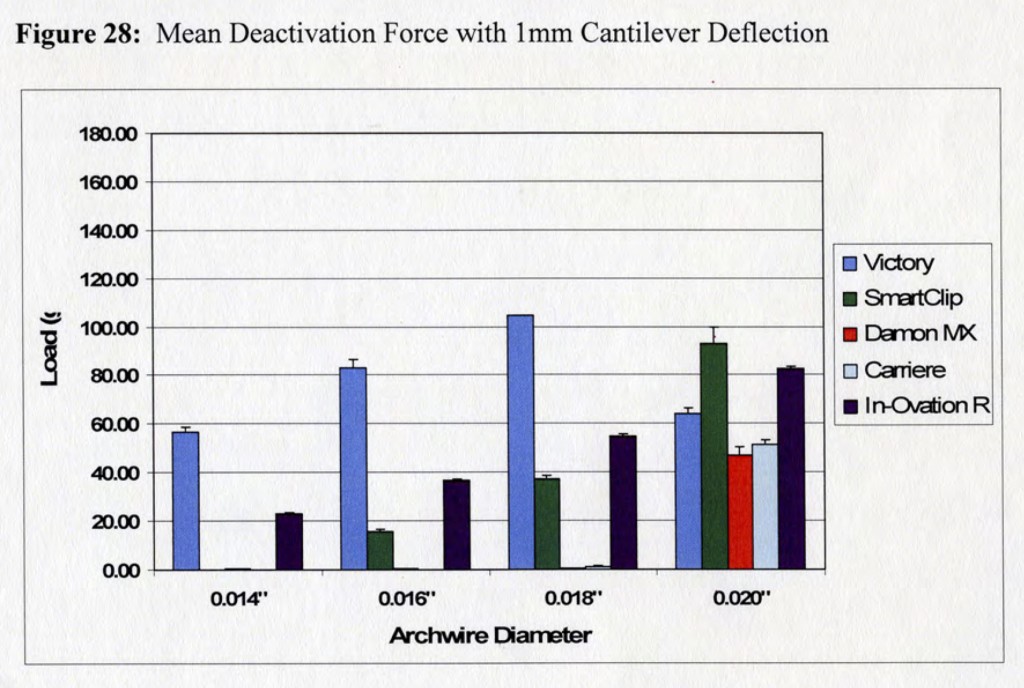

The use of a passive self-ligating brackets rather than traditional elastic or steel ligation, allows doctors to leverage the benefits of maximal intrabracket space during initial alignment, while still being able to gain control during the final stages of treatment. The significance of this intrabracket space is illustrated in a study conducted at the University of Connecticut2, where you can see that with a 1mm in-out discrepancy passive self-ligating brackets remain inactive until an 020 wire is placed.

Naturally, the differences between the various bracket types become less apparent as these 1st order discrepancies are made more severe and as wire diameter increases, but the sweet spot for intrabracket space is simply wider for passive self-ligating braces.

On the flip side, you can have too much intrabracket space. Schudy’s paper outlined their concerns about a failure to adequately fill the bracket slot late in treatment resulting in the expenditure of needless effort and time in the form of repeatedly removing arch wires to place “artistic bends.” This has certainly been the case as of late with some passive self-ligating systems.

But Muh Meta Analysis

Well haven’t systematic reviews and meta-analyses shown no difference with traditional braces? I’m glad you bring that up. These flippant references to systematic reviews or meta-analyses that people love to toss around are not an argument on their own. No one should put their faith completely in the reviewers to properly audit and analyze papers for them. Always double check their assumptions and methods to rule out the possibility of confirmation bias.

The major irony about the Chen article3 being so frequently cited to support the idea passive self-ligating brackets perform no differently than traditional braces is that it is actually an indictment against their own argument.

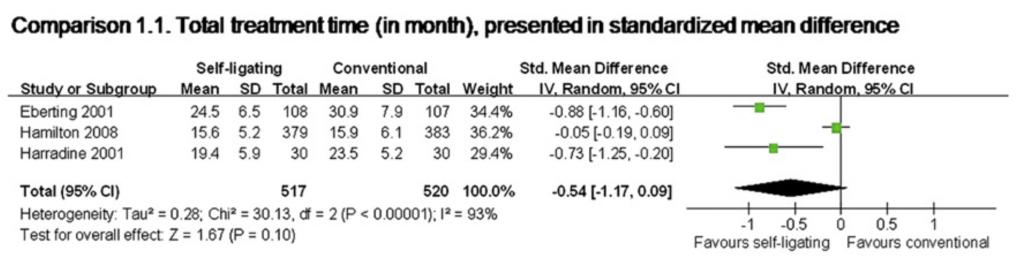

When we take the time to examine their analysis of the differences in total treatment time between self-ligating and traditional braces, we see that they identified three randomized control trials meeting their standards for inclusion in their review. Both the Eberting and the Harradine papers, show a clear reduction in total treatment time with self-ligating braces; however, the inclusion of the Hamilton paper nullifies this result.

I tracked down all three of these papers to look at their methodology, and what I found in the Hamilton paper was puzzling. Although they had a sufficient sample size, they were comparing active self-ligating brackets and single wing traditional braces instead of comparing passive self-ligating braces and traditional twins. Furthermore, the authors stated that “a number of” patients in both groups had Phase 1 treatment with a Herbst or Pendulum appliance, which certainly had an effect on total treatment time since both groups in the Hamilton paper had far shorter treatment times than either of the other papers. This is a big no no. If you are going to pool data together for a statistical analysis, you can’t combine apples and oranges. If the authors were doing their job, they would have excluded the Hamilton paper and their conclusions would show a clear advantage for passive self-ligating braces when it comes to treatment time.

Getting Down to Brass Tacks

Passive self-ligation certainly provides an elegant solution to the dilemma of intrabracket space, but it is not the only treatment approach that takes advantage of these principles. Simply put, we must apply the lessons of Schudy’s paper, and adapt our fixed appliances and our biomechanics to increase treatment efficiency by striking a balance between efficient alignment and controlled finishing. The one thing orthodontists should not be doing is burying their head in the sand because patients are not looking to spend more time in braces or even any time in braces at all.

References:

- Schudy GF, Schudy FF. Intrabracket space and interbracket distance: critical factors in clinical orthodontics. AJODO 1989;96(4):281–94.

- Holbert MB. First Order Archwire Deflections: Comparing Conventional, Active Self-Ligating and Passive Self-Ligating Mechanisms. SoDM Masters Theses 2008:171.

- Chen SS-H, Greenlee GM, Kim J-E, Smith CL, Huang GJ. Systematic review of self-ligating brackets. AJODO 2010;137(6):726.e1–726.e18.