Facemask Fundamentalism

Facemask Fundamentalism

It has been well established that the early correction of anterior crossbites is beneficial for jaw development1 so certainly interceptive treatment to resolve crossbites is advisable. However, there seems to be significant confusion in the orthodontic community about what exactly people are achieving with certain treatment modalities.

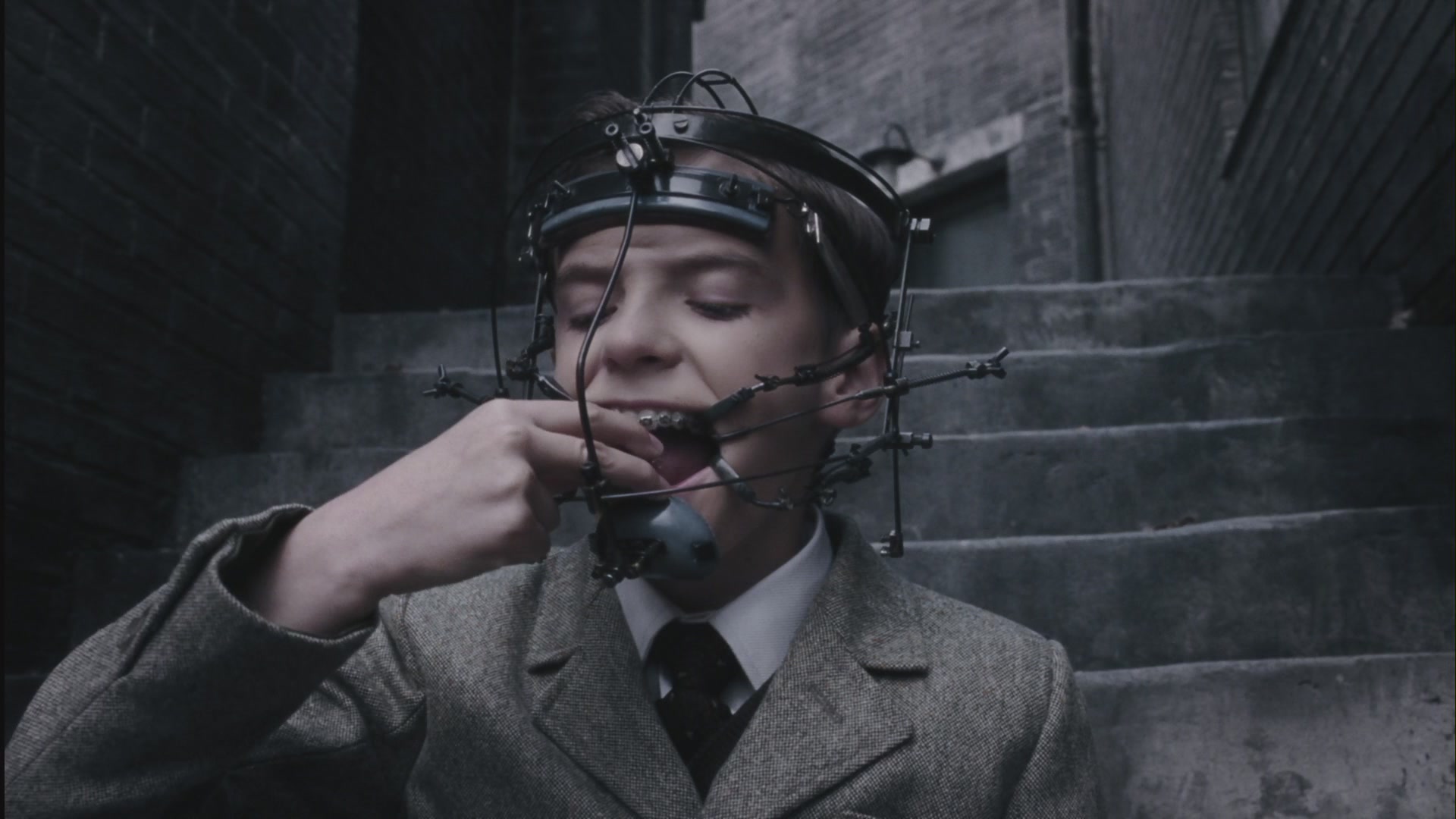

I continue to be astonished by the persistent dogma that reverse-pull facemasks “protract the maxilla” because a comprehensive and unbiased examination of scientific evidence reveals this to be little more than wishful thinking.

-

There is zero evidence of any anterior displacement relative to controls of actual skeletal structures, such as the zygoma, pyriform aperture, etc. with facemask therapy.2,3,4 The sutural strains produced (with or without any expansion protocol) with a facemask are several hundred fold lower than the frost thresholds required for any orthopedic effect based on finite element analysis.5 Why a dentoalveolar landmark like A-point, which is known to remodel significantly in response to both retraction and protraction of the dentition, has served as the basis for assess the “skeletal response” in so many papers makes very little sense.

-

The counterclockwise rotation of the maxillary occlusal plane is a hallmark of dental movement and not an orthopedic effect. The data on Bone Anchored Maxillary Protraction (with infrazygomatic plates) resoundingly confirmed Ricketts proposal that the center of resistance for the maxillary bone (not the maxillary dentition) is at the pterygoid plates. Thus, true orthopedic traction of the maxilla will exhibit a clockwise rotation and not the counterclockwise rotation that we try to mitigate during facemask therapy.6

- Although palatal TADs due to their easy and predictability of placement have been proposed as an alternative means of bone-anchorage, their addition does not improve the effects on the maxilla. In fact, the palatal TADs actually seem to reduce the effects of maxillary traction on A point, backward rotation of the mandible, and any positive dental “side effects” in the maxillary arch.7 Anchoring the dentition to TADs is a strategy that is better suited for hyperdivergent class 3 patients where vertical side effects may be less desirable, but it does not translate into an improved effect on maxillary hypoplasia.

The bottom line is that the clinical effectiveness of a facemask is entirely due to dentoalveolar changes and an improvement in sagittal position of mandible. There is no effect on mid-face, and if that were required then a surgical procedure or bone anchored maxillary protraction should be explored as an option for that patient (though better long term data on BAMP is still needed).

Facemasks are certainly more cost effective to use than many alternatives; however, the same basic outcome that you are prescribing with a facemask can be achieved just as effectively using appliances that facilitate better compliance and are less traumatic to patients.

References:

-

Tollaro I, Baccetti T, Franchi L. Craniofacial changes induced by early functional treatment of Class III malocclusion. AJODO 1996;109(3):310–8.

-

Pangrazio-Kulbersh V, Berger J, Kersten G. Effects of protraction mechanics on the midface. AJODO 1998;114(5):484–91.

-

Arman A. Evaluation of maxillary protraction and fixed appliance therapy in Class III patients. Eur J Orthod 2006;28(4):383–92.

-

Masucci C, Franchi L, Defraia E, Mucedero M, Cozza P, Baccetti T. Stability of rapid maxillary expansion and facemask therapy: A long-term controlled study. AJODO 2011;140(4):493–500.

-

Holberg C, Mahaini L, Rudzki I. Analysis of Sutural Strain in Maxillary Protraction Therapy. Angle Orthod 2007;77(4):586–94.

-

Nguyen, Tung, et al. “Three-dimensional assessment of maxillary changes associated with bone anchored maxillary protraction.” American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 140.6 (2011): 790-798.

- Ngan, Peter, et al. “Comparison of two maxillary protraction protocols: tooth-borne versus bone-anchored protraction facemask treatment.” Progress in orthodontics 16.1 (2015): 26.